Reading Mary Ann in Autumn by Armistead Maupin

Almost 30 years ago, I read the first Tales of the City book.

Today I just finished the eighth book.

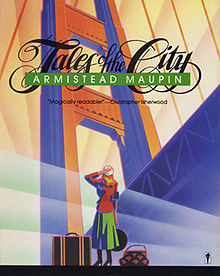

If you don't know the Tales books by Armistead Maupin, read them, in order. I don't know anyone who has said after reading one "Well, that sucked." He wrote the first six books about the lives of the residents of 28 Barbary Lane in San Francisco beginning in 1978 and every two years to 1989, chronicling in fiction life in the city from the wild living of the 1970s through the AIDS-tempered days of the 1980s. With the exception of their landlady/mother figure, Mrs. Madrigal, the main characters were in the midst of their youth in the first six books. He wrote an update to their lives after 20 years in 2007, Michael Tolliver Lives, and the eighth book in the series, Mary Ann in Autumn in 2010.

The characters in this last book, once young adults in their twenties like me when I first read about their lives, are now middle-aged, like me. Almost exactly three years ago I read Michael Tolliver Lives and wrote about what it was like to read about characters in different stages of their lives while in the same stages of my life (though I posted it here recently, I wrote it three years ago). I've read novels featuring characters who age in the course of the work, but usually in the space of a book or a couple books written a year or two apart like the Harry Potter series. But to read about the lives of Michael, Mary Ann, Mrs. Madrigal and others across my adult life is a singular experience. It would be like the now adults who read the Harry Potter books year by year as children reading a novel by Rowling in 20 years about a middle aged Harry, Hermoine, and Ron (unless Ron dies). The closest thing I can think of has been watching the British 7-Up! series over the last 28 years--but not all at once, as your perspective on the narrative changes as you grow older, so it doesn't count if you watch them all at once.

Reading of the effect of separation over time between characters once very dear to each other echoes the separation of former close friends in my life. The feelings of acceptance, regret, loss, and guilt are awkwardly familiar. Their recalling of secrets and grim episodes in their lives brings to mind the same in my own life, with the same mixture of feelings.

Maupin plays with readers' longing for the separate residents of 28 Barbary Lane to reunite as the family they used to be, just as readers dream of reuniting with their old friends, their "family" as they used to be. Several of the earlier books ended with much of the "logical family" gathering together. (Anna Madrigal made a distinction between one's biological family and one's "logical" family, which are sometimes not the same) The gatherings were bittersweet yet never totally tragic. In Mary Ann in Autumn though, as with most real reunions of family, it is death that gathers the people together. The sole comfort in the novel is that real friendships and relationships endure the trials of distance and time. One wonders whether life will mirror art in a similar way.

The choices the characters made in life and their consequences resonate vividly with readers as they look at the choices they themselves made in life. Some actions are forgiven, some cannot be forgiven. Questions of doing the right thing or the wrong thing or too much or too little, of longing for or avoiding the past or future, of maturing or remaining unchanged by time--the subjects of restless nights as we age, figure prominently in the book such as in this sledgehammer yet still true passage:

"It all goes by so fast," Mary Ann thinks. "We dole out our lives in dinner parties and plane flights, and it's over before we know it. We lose everyone we love, if they don't lose us first, and every single thing we do is intended to distract us from that reality."

It reminds me of the famous passage in Paul Bowles' A Sheltering Sky, once read, never forgotten:

“Death is always on the way, but the fact that you don't know when it will arrive seems to take away from the finiteness of life. It's that terrible precision that we hate so much. But because we don't know, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that's so deeply a part of your being that you can't even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.”

Life seemed limitless in the first book in 1976, when the characters were all full of life, as it was for me when I first read the books in the 80s. By the fourth book, death from AIDS was a reality for some characters. By the eighth book, aging and dying was a reality for all of them, as it is for me. Like us, different characters deal with aging in different ways, some trying defy it or run from it, some accepting it. Usually some form of compromise, considered unthinkable when young, is found to cope with reality. Yet facing mortality is a new skill for them and for me. Just as they have lost members of their "family," I have lost members of my "family."

Maupin has promised another book, The Days of Anna Madrigal, this coming January, featuring the characters with whom many readers have travelled through adulthood. I find myself both eager to find out what happens next and not so eager, as death is no stranger in his books as it is no stranger in my life now. To lose a beloved character who you've been reading about your entire adult life is almost like losing a real person. A strange statement, but in this case I have grown to care for the characters as they have lived their lives, just as my relationships with real people are based on living through their lives. Maupin's website features hints about the future book, with characters seeking resolution and peace with their pasts. Before he died, my father once described the people in assisted living facilities: "A bunch of people staring off into space, reviewing their lives." I have to wonder what Anna Madrigal's family will see, and, eventually, what I will see.

Today I just finished the eighth book.

If you don't know the Tales books by Armistead Maupin, read them, in order. I don't know anyone who has said after reading one "Well, that sucked." He wrote the first six books about the lives of the residents of 28 Barbary Lane in San Francisco beginning in 1978 and every two years to 1989, chronicling in fiction life in the city from the wild living of the 1970s through the AIDS-tempered days of the 1980s. With the exception of their landlady/mother figure, Mrs. Madrigal, the main characters were in the midst of their youth in the first six books. He wrote an update to their lives after 20 years in 2007, Michael Tolliver Lives, and the eighth book in the series, Mary Ann in Autumn in 2010.

The characters in this last book, once young adults in their twenties like me when I first read about their lives, are now middle-aged, like me. Almost exactly three years ago I read Michael Tolliver Lives and wrote about what it was like to read about characters in different stages of their lives while in the same stages of my life (though I posted it here recently, I wrote it three years ago). I've read novels featuring characters who age in the course of the work, but usually in the space of a book or a couple books written a year or two apart like the Harry Potter series. But to read about the lives of Michael, Mary Ann, Mrs. Madrigal and others across my adult life is a singular experience. It would be like the now adults who read the Harry Potter books year by year as children reading a novel by Rowling in 20 years about a middle aged Harry, Hermoine, and Ron (unless Ron dies). The closest thing I can think of has been watching the British 7-Up! series over the last 28 years--but not all at once, as your perspective on the narrative changes as you grow older, so it doesn't count if you watch them all at once.

Reading of the effect of separation over time between characters once very dear to each other echoes the separation of former close friends in my life. The feelings of acceptance, regret, loss, and guilt are awkwardly familiar. Their recalling of secrets and grim episodes in their lives brings to mind the same in my own life, with the same mixture of feelings.

Maupin plays with readers' longing for the separate residents of 28 Barbary Lane to reunite as the family they used to be, just as readers dream of reuniting with their old friends, their "family" as they used to be. Several of the earlier books ended with much of the "logical family" gathering together. (Anna Madrigal made a distinction between one's biological family and one's "logical" family, which are sometimes not the same) The gatherings were bittersweet yet never totally tragic. In Mary Ann in Autumn though, as with most real reunions of family, it is death that gathers the people together. The sole comfort in the novel is that real friendships and relationships endure the trials of distance and time. One wonders whether life will mirror art in a similar way.

The choices the characters made in life and their consequences resonate vividly with readers as they look at the choices they themselves made in life. Some actions are forgiven, some cannot be forgiven. Questions of doing the right thing or the wrong thing or too much or too little, of longing for or avoiding the past or future, of maturing or remaining unchanged by time--the subjects of restless nights as we age, figure prominently in the book such as in this sledgehammer yet still true passage:

"It all goes by so fast," Mary Ann thinks. "We dole out our lives in dinner parties and plane flights, and it's over before we know it. We lose everyone we love, if they don't lose us first, and every single thing we do is intended to distract us from that reality."

It reminds me of the famous passage in Paul Bowles' A Sheltering Sky, once read, never forgotten:

“Death is always on the way, but the fact that you don't know when it will arrive seems to take away from the finiteness of life. It's that terrible precision that we hate so much. But because we don't know, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that's so deeply a part of your being that you can't even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.”

Life seemed limitless in the first book in 1976, when the characters were all full of life, as it was for me when I first read the books in the 80s. By the fourth book, death from AIDS was a reality for some characters. By the eighth book, aging and dying was a reality for all of them, as it is for me. Like us, different characters deal with aging in different ways, some trying defy it or run from it, some accepting it. Usually some form of compromise, considered unthinkable when young, is found to cope with reality. Yet facing mortality is a new skill for them and for me. Just as they have lost members of their "family," I have lost members of my "family."

Maupin has promised another book, The Days of Anna Madrigal, this coming January, featuring the characters with whom many readers have travelled through adulthood. I find myself both eager to find out what happens next and not so eager, as death is no stranger in his books as it is no stranger in my life now. To lose a beloved character who you've been reading about your entire adult life is almost like losing a real person. A strange statement, but in this case I have grown to care for the characters as they have lived their lives, just as my relationships with real people are based on living through their lives. Maupin's website features hints about the future book, with characters seeking resolution and peace with their pasts. Before he died, my father once described the people in assisted living facilities: "A bunch of people staring off into space, reviewing their lives." I have to wonder what Anna Madrigal's family will see, and, eventually, what I will see.

Comments

Post a Comment